The Ghostly Politics of Nostalgia

A large panel by artist Lucien Jonas, painted in 1928, welcomes visitors to Versailles Revival (1867-1937).[1] The title and its timescale are precise: between the Second French Empire and interwar Europe, there was a sense of nostalgia, of an ancient ‘Lost Time’ — as in Marcel Proust’s famous words — when people were supposedly happy, peaceful and civilized. In a troubled period, spanning the Franco-Prussian war to the rise of Fascism, artists and writers were impelled to reimagine France’s eighteenth-century images of love and leisure. In the opening painting, we see noblemen and women dancing and playing musical instruments in a garden. To the right, one smaller panel quotes Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing (1767), one of the most iconic Rococo paintings depicting that ‘tasteful’ society.[2]

This ‘graceful’ Rococo imagery, however, was produced within a deeply violent context: the height of modern colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade. What was unique about this period, Professor Simon Gikandi writes,

was that its primary commodity was black bodies, sold and bought to provide free labor to the plantation complexes of the new world, whose primary products — coffee, sugar, tobacco —were needed to satiate the culture of taste and the civilizing process. (Gikandi, 2001: 2)

When the courtly images were revisited two hundred years later, during the period of time presented in Versailles Revival, they were also embedded in a culture of difference, racism, and imperialism. In his panels, Jonas depicts ‘the cultured subjects of modernity’ (Gikandi, 2001: ix) — in contrast to the European fiction of the uncivilized other.

Today, after years of decolonial studies, activism, and public debates on racism and social justice — such as this present issue —, cultural agents might be well aware that those are images of white supremacy. It is therefore problematic to take love and leisure for granted, and exhibiting such works without a critical comment might contribute to support social injustice. As Dr Gloria Wekker puts it, these practices are part of White innocence, which encompasses ‘not knowing’, but most importantly, ‘not wanting to know’ about the inequalities that constitute the ground of Western modernity, thought, and civilization (Wekker, 2016: 17).

Rococo imagery seemed to be out of fashion in France’s artistic and intellectual circles between mid-nineteenth century and mid-twentieth century. As the curators highlight in the text available at the last room,

while it is true that the avant-garde artists at the beginning of the twentieth century were not involved in this revival, Versailles featured in new fashion trends, art de vivre, and illustrations. […] The Roaring Twenties and Art Deco aesthetics enjoyed a new lease of life at the chateau, combining elegance, humour, and sometimes eroticism.

Versailles Revival countered the supposed unfashionability of Rococo imagery French artistic and intellectual circles in the period 1867-1937 and the still canonical history of modern art presented by Alfred H. Barr at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in the 1930s (Barr, 1936). The exhibition successfully recovered a number of artists that were enthusiastic for the Ancien Régime, and produced hundreds of works dedicated to it, among them Jacques-Emile Blanche, Giovanni Boldini, Louise Breslau, Juan Gris and Gerda Wegener. As curator Laurent Salomé explained in the catalogue, the exhibition sought to complicate the established history of modern art by addressing a broader artistic milieu:

The Versailles Revival that we propose to analyze is a social phenomenon. It is more diffuse, more heterogeneous in its manifestations and protagonists. And yet it seems to us to be a very identifiable phenomenon in which all the facets are interconnected. (Salomé and Bonnotte, 2019: 14)

Indeed, it is a complex and intricate social phenomenon, and the exhibition presented different aspects of that Revival, such as foreign politics, social events, literature, etc.; a nostalgia that unfolds into different styles and media. And yet, the curators chose not to investigate the politics of colour — and skin colour — that underlie the visual culture that pays homage to the eighteenth-century Franch court.

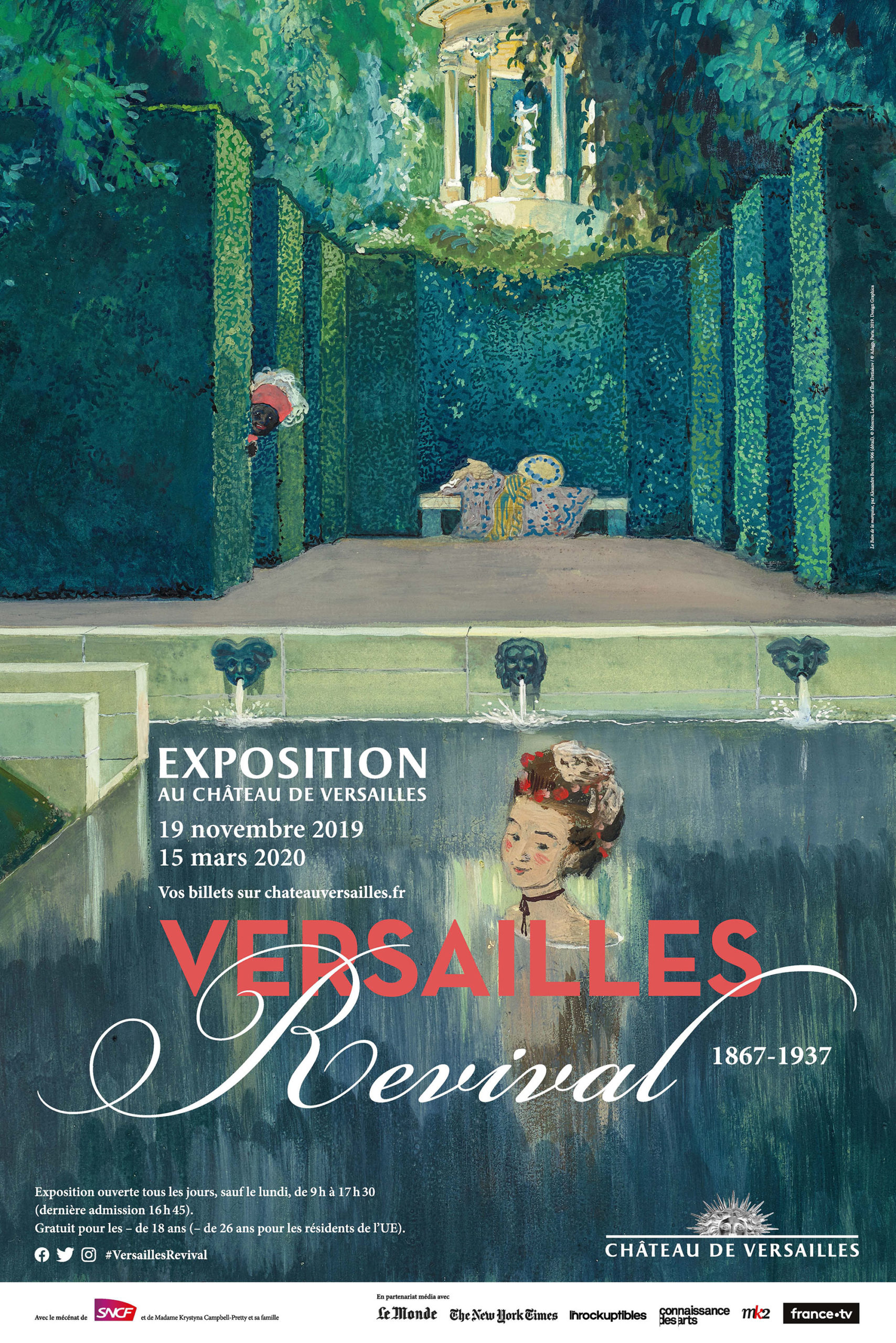

Racial politics were evident in some selected works, such as one of the small gouaches by Russian artist Alexandre Benois: a white marquise bathes, as a black servant sneaks up on her. The artist evokes the Biblical motif of Susanna and the Elders, in which two leering old men surprise a young woman. Not only does the black woman look like the racial stereotype of a ‘mammy’, an African-American nursemaid hired to care for white children, but she is also cast in the role of the sinister character. Not signaled in the exhibition text, this aspect could have passed unnoticed to a visitor who is not aware of racism in visual culture, especially in drawings and paintings. But the image was amplified: it was featured on catalogue cover, the exhibition poster, and in an advertising vignette. Did nobody see this explicit depiction of white supremacy? Or did they not want to see?

In 1906, when Benois made his gouache, it would probably not have raised any protests — in fact, racism was very profitable, and took the form of a mass spectacle throughout the twentieth century. One of the most striking examples is the 1931 Colonial Exhibition organized in Paris,

that staged human zoos at the Bois de Vincennes, attracting 8 million visitors [and had], 33 million tickets sold […], which makes it the biggest event since the Universal Exhibition in 1900. This success proves that a ‘colonial popular consciousness’ was being built, which had recently adopted the ‘white fiction’ (Michel, 2020: 330)

The small painting was on display in a room entirely dedicated to the Russian artist, who according to the label text ‘fell in love with Versailles even before his first visit’. It was beside another similar image, with the same bathing motif and another black servant sneaking. The room was decorated accordingly, with these works on a wall with a trellis, and elsewhere some kind of a loggia, decorated with plastic little leaves. The floor was covered with a green rug, mimicking grass. Hubert Le Gall’s exhibition design echoes Benois’ fantasies of French eighteenth-century court, but seemed oddly fake, as if a world of fantasy could not be possible anymore. Not one word about the racist depictions — as if they were part of that golden age nostalgia.

The following room explores political issues more directly, from a time when Germany invaded France and in 1871 proclaimed the II Reich in Versailles (a disrespectful gesture that would not be forgotten). In fact, the Peace Treaty after the First World War, in 1919, would be signed precisely there, as a direct answer to the defeated Germany. According to the exhibition label text,

This grand hall of Louis XIV was truly crowded for the much-awaited event […]. Its staging constituted an act of revenge for the French who had been humiliated in that same location by the proclamation of the German Empire on 18 January 1871.

Despite the theme of foreign politics, there was also not a word about the European imperialism that led to the First World War, nor the French and German colonial possessions during the Versailles Revival’s framework: 1867-1937.

Throughout the exhibition, visitors are told about the castle’s history, its different restorations over time and the effort to safeguard its collection, with special focus on Pierre de Nolhac, the museum director who in the early twentieth century ‘tried to give back a sense of the Ancien Régime to its spaces.’ But what does ‘Ancien Régime’ mean, in its complexity? Politics are not only about diplomatic meetings or document signing, but root deeply in a nation’s symbolic depictions. Leisure, gallantry, and love — all linked to eighteenth-century monarchy — offer white people a history of their tasteful civilization. It is ironic that one of the rooms that held the exhibition is called ‘Africa’, the continent whose peoples were exploited for centuries, and made possible the richness and the Faust of European courts.

The exhibition also pays homage to the melancholy of Autumn, as a powerful image of a ‘Lost Time’. According to the text on the wall, ‘painters and authors alike were delighted by the beautiful sights which also conveyed a profound melancholy. Indeed, the slow agony of nature echoed the disappearance of a world.’ But at what grounds had this ‘agonizing’ world been built?

After many years of debates regarding visual and material culture, and the politics of seeing, it is striking that an exhibition still celebrates Versailles’ past glory, when it is well known the violence upon which that ‘civilization’ was based. Versailles Revival ghostly glorifies whiteness — with a sense of nostalgia.

Notes

[1] A virtual tour, as well as curatorial and label texts are available at www.chateauversailles.fr/resources/360/revival/index.html.

[2] The painting that inaugurated the fêtes galantes (courtly party) genre was Antoine Watteau’s The Embarkation for Cythera, in 1717.

References

Michel, Aurélia (2020). Un monde en nègre et blanc. Enquête historique sur l’ordre racial, Paris: Seuil.

Barr, Alfred (1936). Cubism and Abstract Art, New York: MoMA.

Gikandi, Simon (2011). Slavery and the Culture of Taste, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Salomé, Laurent and Bonotte, Claire (eds.) (2019). Versailles Revival, 1867-1937, Versailles: Château de Versailles.

Wekker, Gloria (2016). White Innocence. Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race, Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rosalind McKever and Manuel Neves for sharing their thoughts on the exhibition.